Judith Geichman

Atmosphere

May 27 - July 9

Atmosphere

May 27 - July 9

There’s a notion of the atmospheric that perceives it as a singular, cohesive flow, when in actuality, anything that we might consider to be an atmosphere, or reflective of its qualities, is the result of varying forces and materials, the combination of which might just as well be described as combustable as it would cohesive. Such is the case with Judith Geichman’s sense of atmosphere as it applies to her new work. Comprising paintings both large (84 x 118 inches) and small (20 x 16 inches), this exhibition offers work that invites exploration by the viewer in alignment with Geichman’s own explorations as a maker who both instigates and responds to the formal and material qualities of these paintings. The atmospheres that are generated are the results of a process that is dualistically engaged through a balanced acceptance of the constructive and destructive as defining frameworks for the act of painting, Judith’s acts of painting. To paraphrase Francesco Bonami when addressing the work of Rudolf Stingle, the act of painting itself is not enough to yield a painting—the painter must be assessing and making further decisions that shape the painting through the act of looking. Construction, deconstructing; acting, looking.

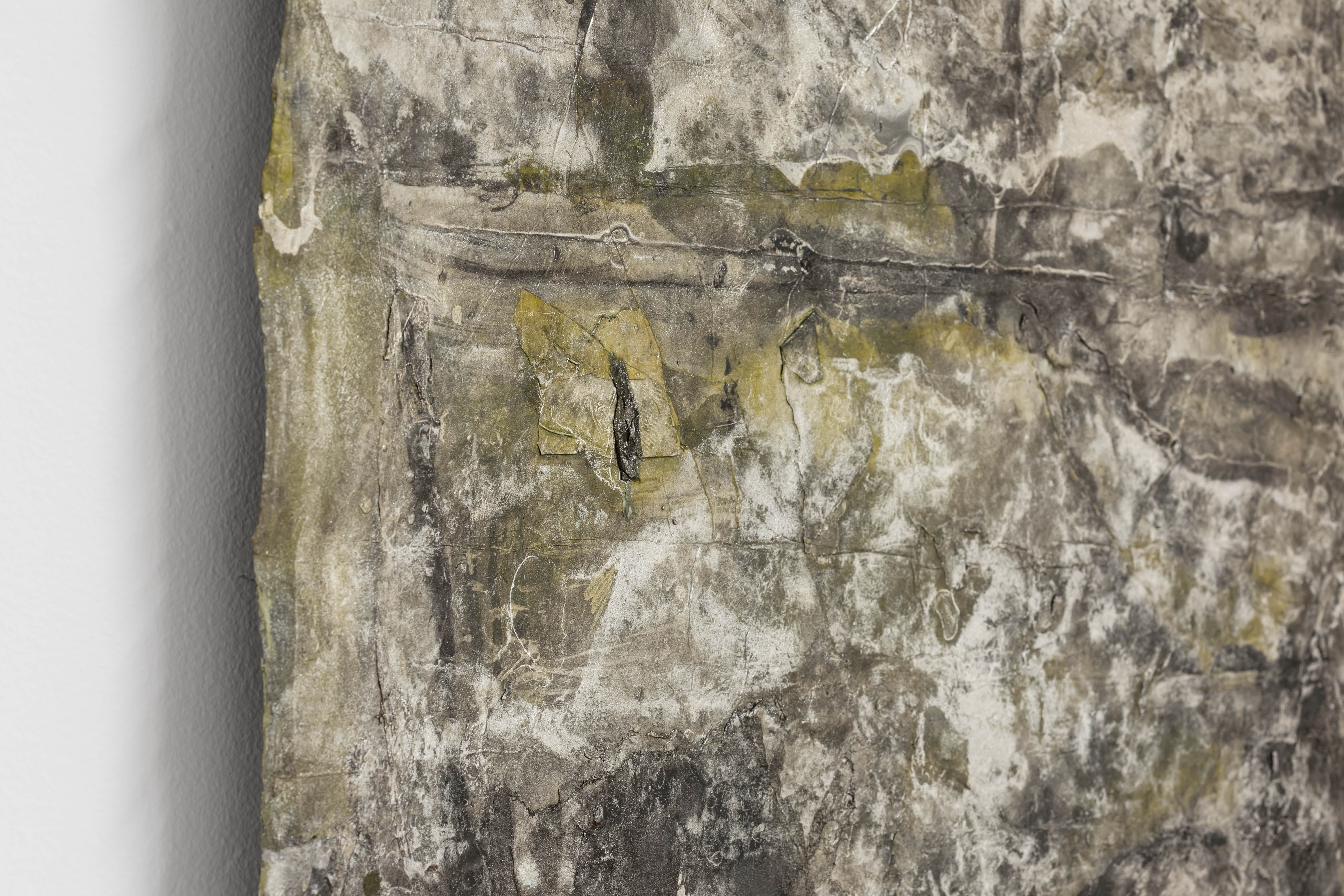

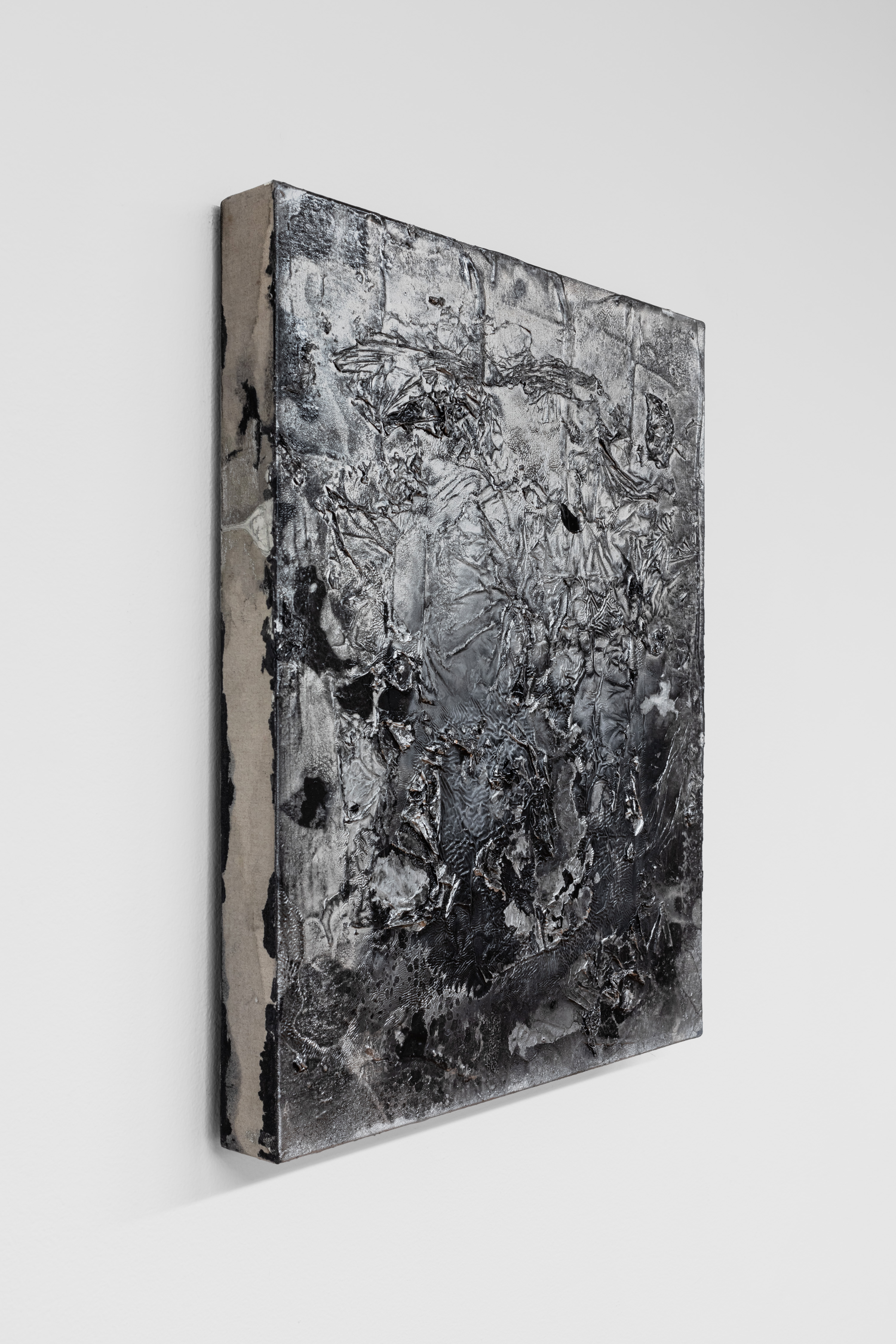

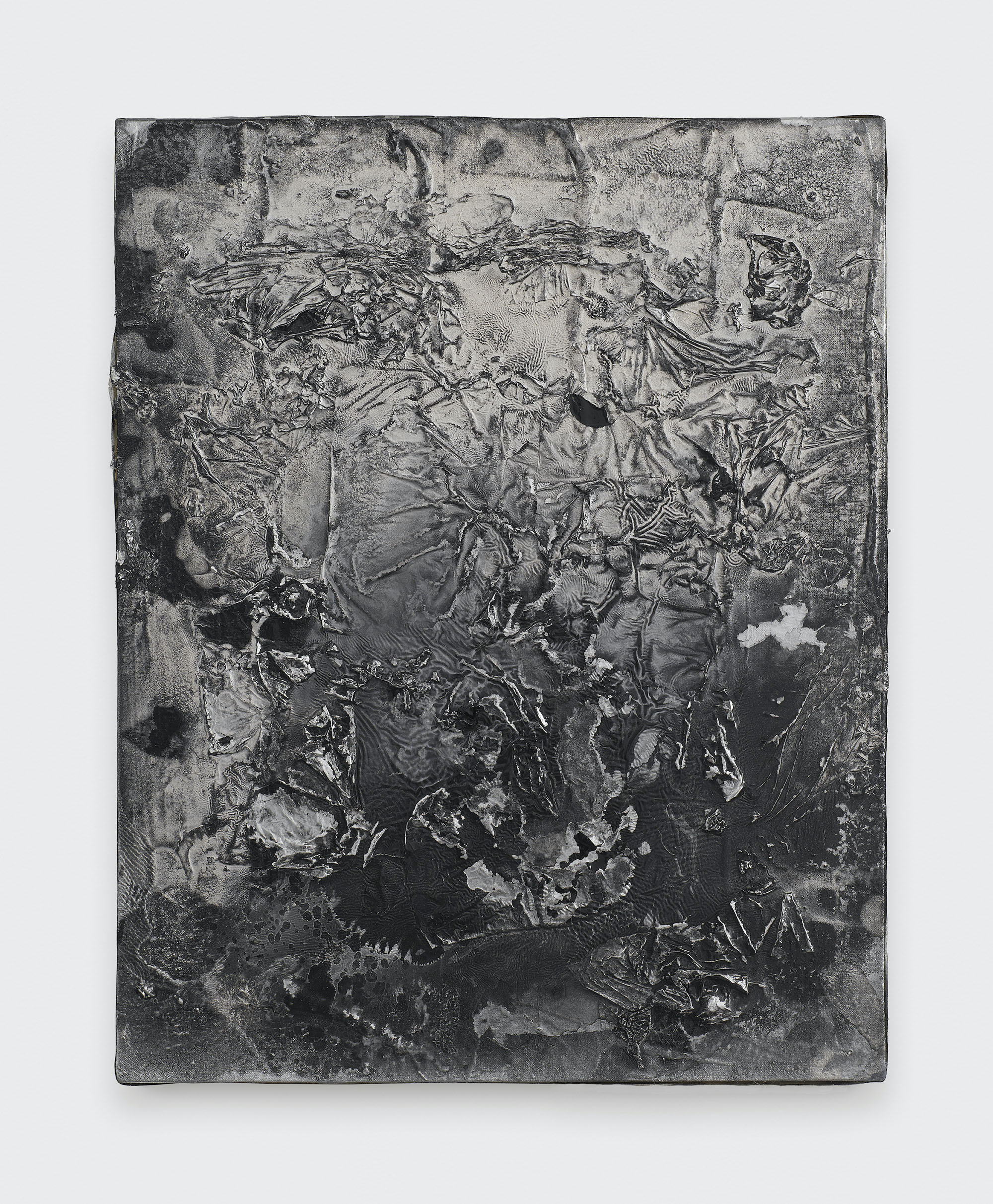

That which constitutes the act in Judith’s work happens almost completely on the floor. Stretched and un-stretched surfaces (canvases and panels, and more recently linen and both hanji and Yupo papers) lay about the floor of the studio at various stages of production. Layers are built up and removed with intention, done and undone, typically through a multitude of materials, tools, and applications. Paints are poured, sprayed, or otherwise moved about, then added to or removed through scraping, extracting, or folding, at times interfering with drying paint as it attempts to settle into a composition before decomposition forces an adjustment, putting Geichman the painter (acting and looking) in a position of uncertainty. Each painting becomes its own atmosphere while also functioning as components of a yet larger atmosphere that is the studio. As much as Geichman’s paintings must be looked at as autonomous paintings, they are also products of their environment, and reflect the activities of the studio in a way that transcends the defined boarders of each painting. A natural cross-pollination has developed over the decades of Judith’s production, which has more recently allowed for scraps of other paintings (intentionally and accidentally removed) as well as studio detritus to find their way directly into the works. This is seen most evidently in her 20 x 16 inch works on linen, a size of painting that has established itself as a recent motif of scale in Geichman’s work. Thick patches of painted and collaged elements intersect with remnants and marks of their removal. Although the slowly built up faces of these paintings might still reveal glimpses into prior attempts and versions beneath, the edges offer another look into the complex lives these paintings have lived through Geichman’s acts, where forms, colors, and materials with no presence on the face can sometimes be found.

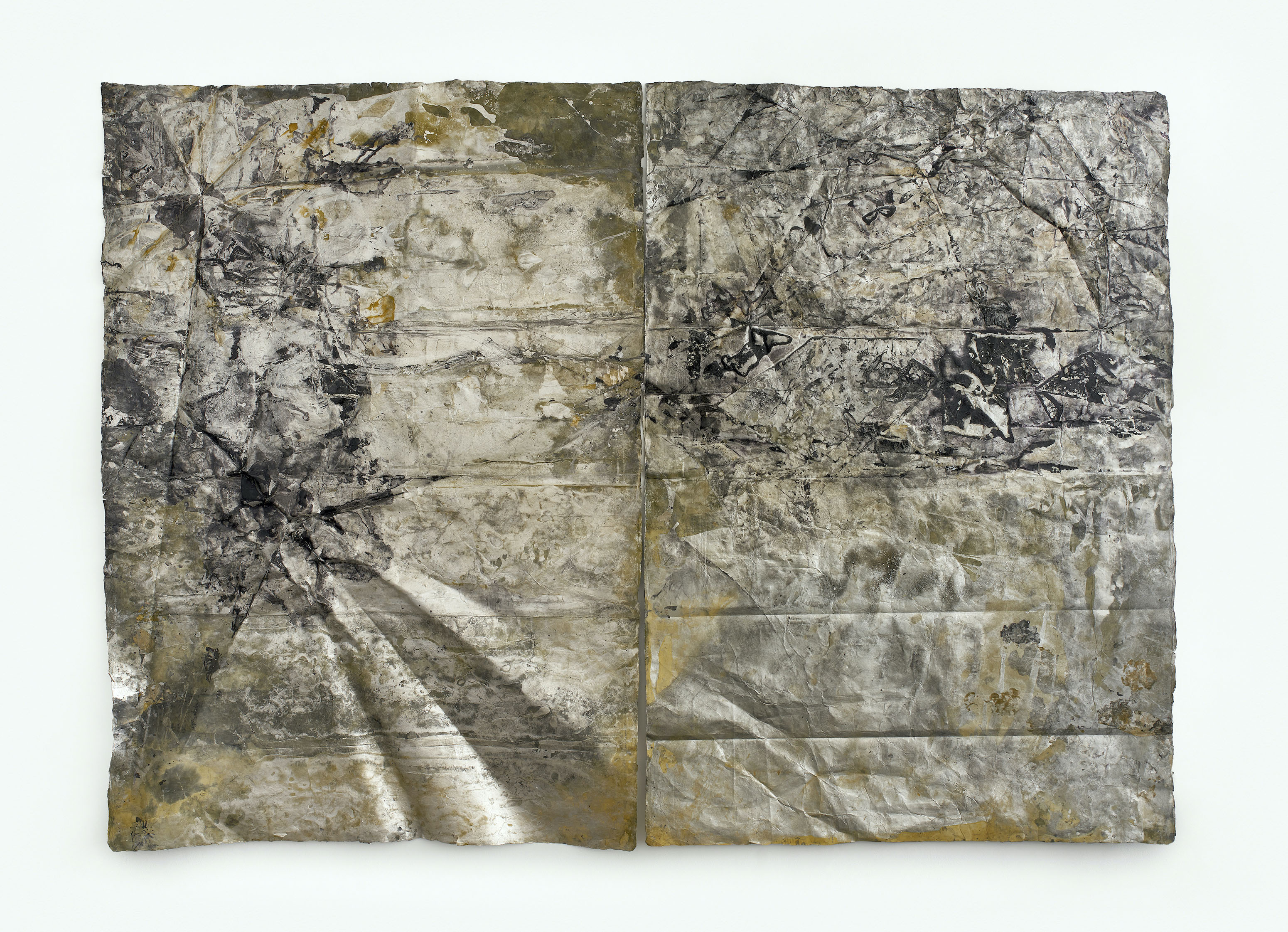

It’s clear that a different set of responses is at play in the acts that guide the production of Geichman’s works on hanji paper. These large format pieces (84 x 59, or 84 x 118 inches) exhibit more subtle surface differentiations in terms of paint, but disrupt that relative uniformity by retaining the crinkles and creases of Geichman’s physical alterations of the material. As with all the others, painting on the hanji sheets happens on the floor through a number of applications. Owing to its long-appreciated durability (hanji has been made in Korea for centuries), the paper is able to come back from Geichman’s aggressive manipulations, while still retaining evidence of them. As a result, the now wavering and textured paper surfaces combine with the paint (some of which appears metallic) to create an inexhaustibly varied field, the appearance of which shifts in response to the conditions of light they are seen in. They are finished, and never finished.

The dualistic life these paintings possess defines every point of their timelines. What gets known, becomes unknown; the seen becomes unseen; construction through destruction; damage intertwined with resilience; cohesion into combustion. In the end, we have paintings; paintings that maintain an open and living presence as we look upon them, completing an act that will never end.

Untitled, 2018-2022, acrylic, enamel, spray paint on Yupo Paper, mounted to Di-bond, wood frame, 78 x 59 inches

Untitled Diptych II, 2022, acrylic on hanji paper, 83 x 118 inches

Untitled, 2021, acrylic and mixed media on linen, 20 x 16 inches

Untitled, 2022, acrylic and mixed media on linen, 20 x 16 inches

Untitled, 2022, acrylic on hanji paper, 84 x 59 inches